Oct 06, 2014 8 Questions With: Katrina Spade / Urban Death Project

Intrigued by the Urban Death Project, I reached out to founder Katrina Spade to learn more about the solution she created in response to the overcrowding of city cemeteries. She developed a sustainable method of disposing of our dead and a new ritual for laying our loved ones to rest. The Urban Death Project utilizes the process of composting to safely and gently turn our deceased into soil-building material, creating a meaningful, equitable, and ecological urban alternative to existing options. While death is an often undesirable topic, Katrina is approaching this cycle of nature in an strikingly practical way.Katrina has focused her design career on creating human-centered, ecological, architectural solutions. Prior to architecture school, she studied sustainable design and building at Yestermorrow Design Build School, with a focus on regenerative communities and permaculture. While earning her Masters of Architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, she received a grant from the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture to build and monitor a compost heating system, a project which helped initiate the Urban Death Project. Katrina earned a BA in Anthropology from Haverford College, and a Masters of Architecture from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She is an Echoing Green Climate Fellow.

Describe how you concepted Urban Death Project to solve a significant problem in burial sustainability.

I was in graduate school for architecture, and I’d been thinking a lot about how decomposition is generally feared and avoided in our culture. Without decomposition – where microbes break organic materials down into soil – we humans would be toast. It’s an amazing process – turning dead stuff into soil – and I began to think about how it might intersect with architecture. At the same time, being thirty-something, it suddenly dawned on me that I was actually going to die someday. I began researching the options we have for the disposal of our physical bodies, and I found that both conventional burial and cremation are wasteful and polluting processes. So I set out to design a new method, using the process of composting as a basis for the design.

Where do you hope to take Urban Death Project in the long run, after the successful prototype?

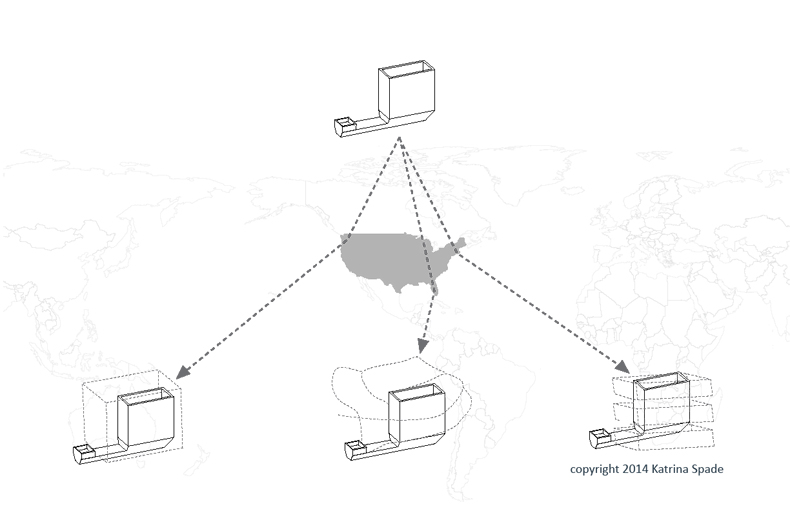

Right now, we are working on the design and engineering of the system that will compost bodies, and we plan to build a prototype in the next few years. At the same time, we are creating a franchise kit to help others – municipalities, individuals, and organizations – build Urban Death Projects in their neighborhoods in cities all over the world. We’ll provide the specifications of the system itself as well as a framework for ritual and the programming requirements for each building, and different architects will design each Urban Death Project. That part is very important – each project should be specifically designed for the community which it serves. I liken it to a library branch – each is unique to its neighborhood but you know what to expect when you enter one.

What are some of the milestones achieved that you are most proud of?

Becoming an Echoing Green Climate Fellow was a huge accomplishment, and has really propelled the project forward in an exciting way.

What does your typical workday look like? Do you work on other projects?

I only work on the Urban Death Project, and it is more than a full time job! On a typical workday, I will respond to requests for press information or potential collaborations with others. I might take a few hours to work on our strategic plan, or think about how to inspire people to get involved. I’m usually working on a grant proposal at any given time. Today, I’m working on memorizing my four-minute pitch for next week’s SXSW Eco Startup Pitch Competition.

As an entrepreneur of a not-for-profit company (with the intention to disrupt the $11billion funeral industry), what are some of the challenges you have faced and associated learnings?

Fundraising is a huge challenge for us as a not-for-profit. I believe in my gut that there is money out there to support this type of audacious, game-changing project, but finding it and asking for it takes some time. Right now, I am setting up the organization to be as efficient, lean, and effective as possible, so that philanthropists will be excited to partner with us.

How do you approach changing consumer behavior and building acceptance for the concept?

The currently accepted methods for the disposal of the dead have come to us almost accidentally – part historical convention and part funeral industry mandate – and I think that our society is ready for a change. In popular media, we are seeing evidence of a movement to own our own deaths and to simplify them, as well as to make them more sustainable. There is no reason that we should be turned over to a for-profit industry once we die. Our bodies are full of potential!

We are also seeing evidence that urban dwellers desire a deeper connection with the natural cycles, and that they want to be part of the solution to our environmental dilemma. The rise in popularity of urban farming, permaculture, and the use of city infrastructure to produce food and energy (such as rooftop gardens, aquaculture, urban green space and solar power) are examples of this. The Urban Death Project goes hand in hand with these movements – it is riding an enormous wave of momentum. Together, we will create an ecological, equitable, and meaningful alternative to death care.

As a kid, what did you aspire to be?

As a kid, I thought I’d probably become a doctor, since so many of my family members are in medicine. We had plenty of conversations about death and dying at the dinner table. I guess it makes sense that I am doing this work, but from a design perspective. I love this work, but it definitely never occurred to me that I’d be doing this when I was young.

Where do you personally find inspiration?

I am excited about the work being done in my community right now around prison abolition and the dismantling of immigrant detention centers. Talk about an amazing design challenge – envisioning a world without prisons or borders!

Permaculture and whole systems design are also passions of mine. Beautiful design – the kind that is elegant in its simplicity and completely accessible – inspires me.