Jan 14, 2014 Book Club

I recall one of my English professors at UCLA saying in a lecture that you can’t read every book in the world but you can skim the book reviews in the Sunday paper to at least know what’s going on. In that spirit–and in contrast to actual criticism–here are some thoughts on key books that I pulled off my bookshelf.

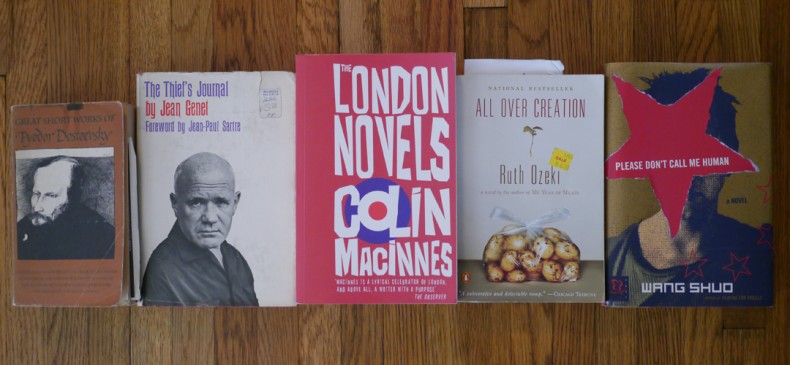

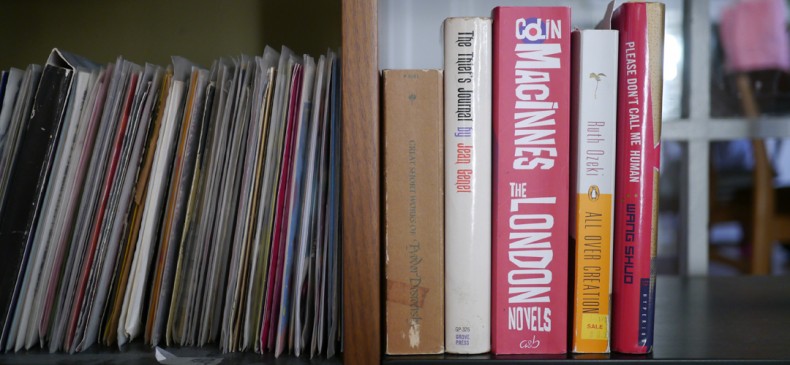

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Great Short Works

Although the great Russian novelist is known for lengthy works such as Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamozov, I prefer his short stories. Perhaps I have a limited attention span, since I also like David Foster Wallace’s essays more than his famous brick-like novel. (It doesn’t hurt that Dostoevsky’s shorter pieces aren’t as bogged down with religious baggage.)

I purchased this used paperback for a class on Russian Literature in Translation, which actually cemented my decision to be an English major at UCLA. As an undeclared sophomore who liked punk rock and exploitation, horror, and b-movies, I was naturally attracted to the antiheroes of Notes From The Underground, The Gambler, and The Double. And when I saw that my essays about the dark psychodramas were ruining the curve for the Russian majors in my class, I realized that literature would be my focus in college.

Jean Genet, The Thief’s Journal

I distinctly remember buying my used copy of the first edition of the Grove Press hardcover at the infamous Amok store on Vermont for just 7 bucks. The Los Feliz bookshop was best known for having shelves dedicated to the likes of Jack Parsons, Anton LaVey, and Tom of Finland, as well as a kick-ass reader that they released every couple of years. After graduating, I was ready to read something outside of the Norton Anthology.

The Thief’s Journal intrigued me because David Bowie’s “Jean Genie” was allegedly named after the author, and then the storytelling proceeded to blow me away. While the topics are as dark as can be–hustling, stealing, backstabbing–the tone is pious and practically otherworldly. In that way it’s more like a Smiths record than the Bowie track, imbuing the darkest of subject matters with an oddly sunshiny tone.

Colin MacInnes, The London Novels

For a guy like me who has always lived in Los Angeles, reading City of Spades, Absolute Beginners, and Mr. Love and Justice isn’t that different from reading Shakespeare. It’s so full of impenetrable British slang that I really needed to concentrate to dig in. Imagine turning to a random chapter of A Clockwork Orange without using the glossary.

Of course it’s the central book in the London Trilogy that is best. That’s the one The Jam wrote a song about and Julien Temple adapted into a movie starring David Bowie and Sade. Based on the rise of teen culture, black culture, and the industries that surrounded them in working-class England during the ’50s, Absolute Beginners is an amazing pre-Mod time capsule, and a more urban, claustrophobic, and tense counterpoint to Kerouac’s looser counterculture fiction written around the same time in Beat America.

Ruth Ozeki, All Over Creation

This is the newest and slickest book of the bunch, and I love how the Canadian-American novelist carries on the social conscience and tradition of Dickens and Sinclair. She takes on agribusiness and genetic engineering without sacrificing lively characters or storytelling. It’s a page turner as much as it is a muckraker.

For a time documentary movies seemed to be the catalyst of choice for social change. But now that they’re primarily used to bolster the careers of under-appreciated rock bands (which I have no problem with) books like All Over Creation seem to be the way to go. That’s why I interviewed her for Giant Robot mag, which didn’t feature much literature. I thought she was doing something cool.

Wang Shuo, Please Don’t Call Me Human

When the translated novel was released in the U.S., movies from China were still pretty square compared to Hong Kong cinema, Contemporary Chinese Art hadn’t taken off, and interesting Chinese fiction was pretty much limited to the acclaimed (but traditional) martial arts novels of Louis Cha. I purchased a hardcover edition of Please Don’t Call Me Human on a whim and it blew my mind. Wang fearlessly and surrealistically pokes fun of nationalism through sports, gender roles, faith, and politics with bold strokes that come across more like John Waters than Chuck Palahniuk.

This book impressed me so much that when my efforts to track down and feature Wang in Giant Robot failed (turns out the bad boy celebrity author quit fiction for filmmaking because the latter is easier, more fun, and more profitable) I contacted the interpreter, Howard Goldblatt, interviewed him, and began to seek out other books that he worked on!

Looking back it’s strange to imagine a time when I’d treat books like records–in which one new favorite leads to a feverish search for another. And even stranger that the books are ordered alphabetically yet somehow tell my story. Sadly, these half-baked reviews reveal more about me than the books.