Mar 18, 2016 End of Summer

It is with great pleasure that I share the announcement of a very special project developed and produced with Imprint Culture Lab. In the Fall of 2014, Julia Huang and I met in Portland, Oregon to discuss the seed of an idea that would take shape through close collaboration over the next year and a half. Boiled down to its core, the idea was very simple- to create a long term initiative that would benefit and support the coming generation of emerging contemporary artists from Japan. The context surrounding this idea however, is much more rich as to why we believed this was the right moment for such a project.

We began by looking backward together, at the art that was being made in Japan’s crucial postwar period, roughly between 1950 and 1970. Two undeniably complex, fruitful, and thrilling artistic decades for Japan in which the backdrop of the country’s defeat in World War II, and the subsequent economic reconstruction and reconsidering of cultural ideals propelled a wave of radically experimental art practices. Communal experiences and group exchange between artists played an important role, as this era saw the emergence of artist collectives such as Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop), Gutai, Hi-Red Center, Tokyo Fluxus and more loosely, Mono-Ha (School of Things).

In the middle of this period, Tokyo hosted the 1964 Summer Olympics, reemerging on the the world stage as a peaceful and rebuilt nation less than twenty years after the end of World War II. Along with Expo ’70 in Osaka, these events became the impetus for socially and politically engaged art that was critical of the perceived nationalistic air surrounding the events, and in many ways exemplifying the radical spirit of the time.

Our current project is not overtly tied to this period of art history, but in thinking broadly about a time in which artistic production in Japan was at an exciting turning point, we were led to consider what local, national and global conditions that current and future artists in Japan might be facing and interpreting through their work. In 2020, the Olympics will return to Tokyo once again, becoming the first time an Asian country has hosted the games twice. As the Olympics bring the eyes of world on Japan once more, and with the 1964 Olympics being so inextricably linked to a vital period of Japanese art, we wondered, what will artists in Japan be creating in 2020?

At our first meeting, Julia and I sat together in Portland’s Pearl District with the Portland Japanese Gardens up the hill to our west, and the neighborhood which was once the city’s Japantown to our east. With our discussion quickly developing into the idea of hosting Japanese artists here in the U.S., the answer to the question of where was beneath our feet. Having been raised in both Portland and Japan, I have always understood the ways in which the two seemingly disparate places overlap in both concrete ways and ways better felt. Portland has always felt like something of an in-between, or a gateway between the constructs of “East” and “West”. It is possible this view is hinged mostly on an emotional connection to my own childhood of traveling back and forth, but as more friends and colleagues from Japan visited over the years describing their sensations of an instant familiarity, the more sure I become.

In thinking about “East” and “West” dualism and the nature of our budding project, I also turned to art historian Reiko Tomii’s writing on the concept of “international contemporaneity” and its assertion that “looking alike does not necessarily mean thinking alike.” Saddled especially under Modernist emphasis on originality, there once existed a long held criticism and misunderstanding, often by Japanese art critics themselves, of Japanese art in the 1960s being derivative of Western art. The “catching-up mentality” was seen as the quest to become as good/original as European and American art.

Tomii explains the short-sidedness of this, and the central idea of “international contemporaneity” in response, by saying:

“Ultimately, the competition of “Who’s the first”—and a narration of history based on this competition—is futile, because there almost always exists a prior instance somewhere in this vast world, characterized by “contemporaneity” and “multiplicity”… which points to the limitation of formalism and the need for different ways of looking—not just looking at the surface (style) but understanding at the concept and context beneath the surface of similar-looking works—in order to evaluate their similarity and to differentiate them.”

Though the question of to what degree aspects of the “catching-up mentality” still exist today is beyond what I say, it nevertheless led to a desire to purposefully not want to conduct our project in a Western art capital. The idea of bringing Japanese artists to the U.S., to participate in an art program in an unexpected but meaningful city became exciting to us as a way to facilitate a highly aware exchange, yet out of the reach of the dominant voice.

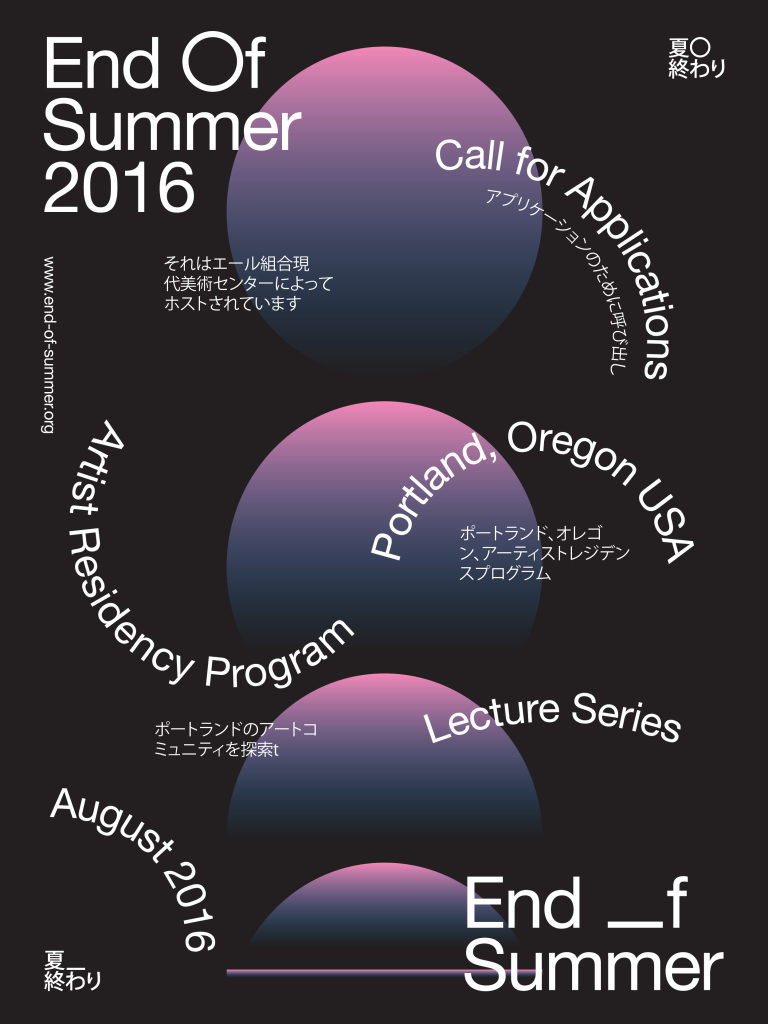

What we decided to develop is a two part, cross-cultural cross-cultural art program called End of Summer– comprised of an annual summer residency for emerging Japanese artists, as well as a series of public lectures and presentations. End of Summer will be based out of the Yale Union contemporary art center building in Southeast Portland, Oregon.

End of Summer seeks to build a dialogue between the Pacific Northwest and Japan through contemporary art. Each year, a group of up to six Japanese artists and art students will be selected through an open call, and one Japanese curator or writer will be invited to participate in the program. The residency utilizes the setting of Portland, with its cultural ties to Japan, community oriented ethos, and dynamic arts activity, as a site for creative exploration that nurtures an international connectivity.

End of Summer emphasizes an exploratory and research based experience, without demands for artistic production. Upon arrival in Portland, resident artists will be provided with studio space to act as their home base, from which they can research, experiment and work. The crux of the program however is centered on a series of activities and events organized to allow residents the opportunity to interact with Portland’s art community directly, including exhibition and studio visits.

Each week the program will also host a guest lecture- public events organized specifically for the residency. Participating lecturers are notable in diverse fields of study, selected for the program to encourage a perspective that is international and critically engaged. Each of the lecturers and their work are also directly investigating, or informed by Japanese sensibilities or history, crucially framing the western-set residency in eastern points of view.

The residency culminates in a roundtable discussion and open studio event. The roundtable provides an opportunity for the artists to share their impressions on what they have seen and experienced, which will be documented in a book project with Portland’s Publication Studio, as well as online, as part of an ongoing effort by the program to collect and disseminate more perspectives from Japanese artists. During the open studio, the public is invited into the residents’ workspace at Yale Union to view works in progress or travel findings, and enjoy a social closing out of the program.