May 24, 2016 Wong Kar Wai in person at the Academy and new book with John Powers

Right after graduating from UCLA, my old roommate Jeff and I got hooked on Hong Kong movies. We’d drive out to the San Gabriel Valley once but more often twice a week to catch double features at the Garfield, Bridge, Kuo Hwa, Huo Hwa, and a few other big screens that came and left. It was great. It cost just five bucks to get in and there was stuff like dried mango, shrimp chips, and hot tea in Styrofoam cups at the concession stand. Did I mention that directors like Tsui Hark, John Woo, and Wong Kar Wai were out of their minds? Getting to see Chungking Express and Ashes of Time in a Chinese movie theater in 1994 before Wong made the jump to arthouse distribution was pretty awesome.

It shouldn’t have surprised me that Jeff would become a film archivist for a living since he has has kept and catalogued every single ticket stub, flyer, and calendar picked up at any movie he went to since before we met. But who knew he would invite me to see Wong Kar Wai in person at the Academy of Motion Pictures more than 20 years later?

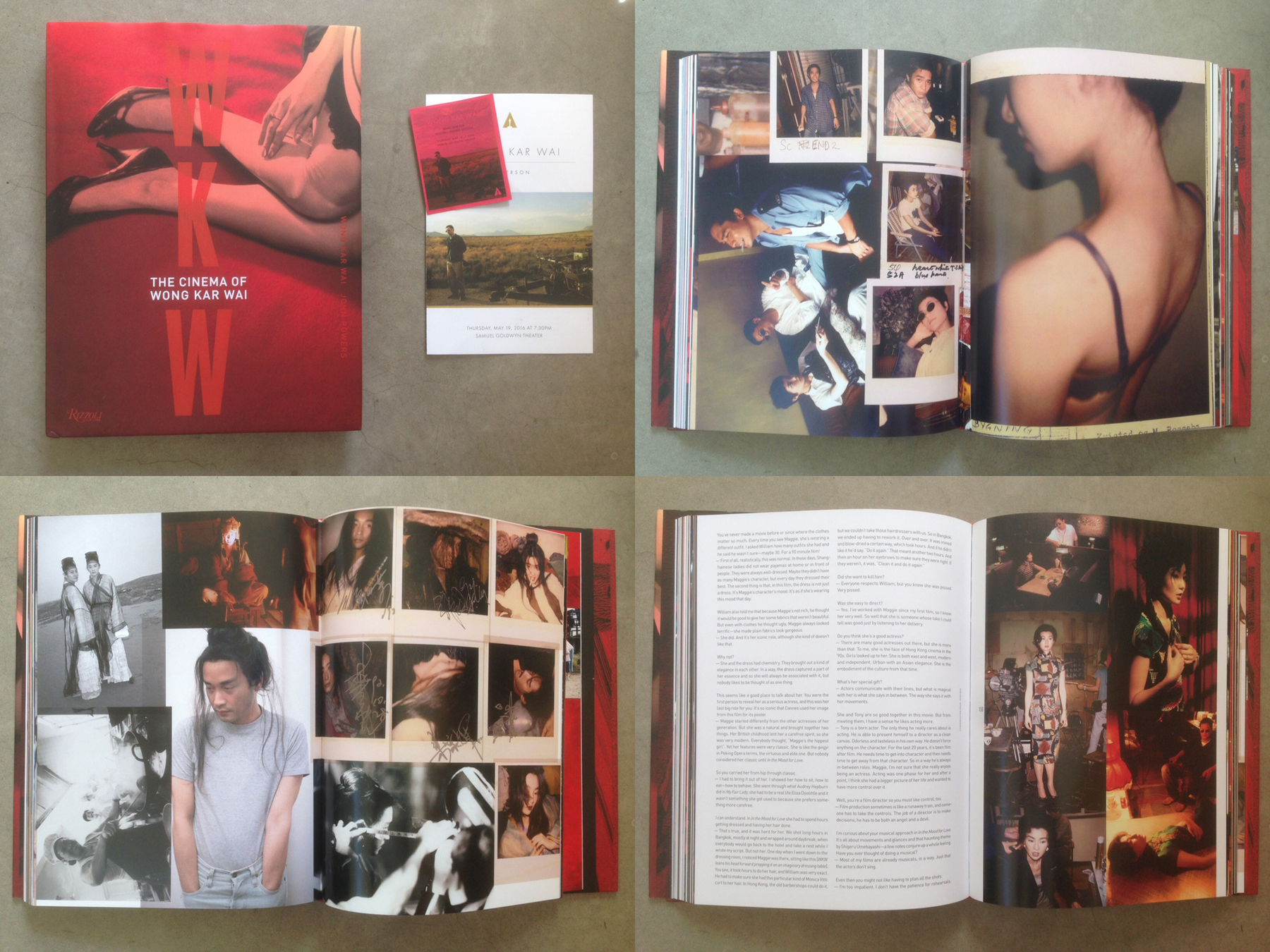

The event was thrown to celebrate the release of a book by Rizzoli co-authored by Wong and local film critic John Powers. Jeff and I cornered Powers during the reception and told him that we were big fans of his movie reviews in the L.A. Weekly back in the day. There wasn’t a lot of mainstream coverage of Hong Kong movies back then, and it’s great that he has gone on to do work for NPR and Vogue. Powers is a cool guy. We gushed about Hong Kong movies and asked for the scoop on what it was like working with the famously late director. He said that everything we’ve heard about Wong is true–and that it was a pleasure to collaborate with him.

The Cinema of Wong Kar Wai is as beautiful as it is comprehensive with six lengthy conversations between the journalist and filmmaker that start with Wong’s childhood as an immigrant kid from Shanghai in Hong Kong who had a nightclub-owning dad and mom that took him to the movies religiously and go all the way to him being a celebrated guest at Cannes. You’ll find everything you ever wanted to know about his film-making philosophy (every film should be different), his relationships with partners (Christopher Doyle, Maggie Cheung, Tony Leung), and his outlook toward art (and commerce), and Powers comes across as vastly knowledgeable and intimate without being an obsequious know-it-all in any way. Wong is honest and often funny. They are not afraid to push each other’s buttons, which makes for interesting as well as informative reading. Oh, there are amazing photos laid out by longtime design partner Wing Shya, too.

The first half of the the event entailed Powers showing clips and then providing his observations about them. It must have been fun but couldn’t have been easy to decide on which ones to show, but he sampled Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express, Fallen Angels, Happy Together, In the Mood for Love, and The Grandmaster. What a treat for us to see the segments in gorgeous grainy, saturated color (some lovely B&W for Happy Together) on a big screen in a dark room with great sound: the colors, the music, the atmosphere… With the filmmaker in the audiences, some of Powers’ comments came across like a roast! I would paraphrase some of his thoughts if there wasn’t a great book that true fans should purchase and read.

The final clip shown taken from the Madmen TV show was full of familiar color, smoke, and style. And then co-creator Matthew Weiner came out to chat with Wong. Technique was a recurring subject, such as the stylized chase scenes in Chungking Express (cool looking, conducive to guerrilla filmmaking, and totally obsolete now that it can be done as an after effect) and his reputation for making up dialogue on the spot (actually the morning of) because he doesn’t enjoy writing. When Weiner said he didn’t like to write, either, Wong poked fun at him by saying that wasn’t true because he saw all the fancy pens at the Madmen office. Another fun moment occurred after Wong, who learned the art under the tutelage of directors like Patrick Tam, dismissed film school as unnecessary. Weiner told him not to say that in front of his kids who were in the audience.

Perhaps the sweetest moment came toward the end, after Wong said he agreed to make the book with Powers because he thought he wouldn’t have to answer questions about his work anymore. Of course, there he was talking about his movies again. But then he added that the book was also for his 21-year-old son who was just graduating from college. Filmmakers like Wong leave home for months or years at a time to make a movie. This book was also dedicated to his son and intended to inform him what his dad was doing during all that time away.

Of course, it is also a gift to hardcore fans like Jeff and me. We had stalked him two decades ago at a UCLA screening two decades ago when Tarantino got involved with distributing Chungking Express in the U.S. We snagged a picture of him in Westwood and got another photo with him at the Academy. Some things like art, friendship, and obsessive fandom never die.

See movies in theaters and follow Imprint on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, too.